Rudyard Kipling was born in India, 'the jewel in the Crown of the British Empire', in 1865. His life straddles the turn of the twentieth-century almost exactly (he died in 1936), a period that also saw the British Empire reach its height and begin its decline -- Indian independence came little more than a decade after Kipling's death in 1947. The contrasting locations of his birth (the first six years of his life were spent in the multicultural and vibrantly bustling city of Bombay) and death (the rolling green, and quintessentially 'British', countryside of Sussex) epitomize the paradoxical nature of Kipling, the literary man. Where so many of his writings set in India exhibit a zest and enthusiasm for Eastern culture, landscape, and peoples, an equally large number of his poems are filled with racism, pro-imperial jingoism, and an undying belief in the white man's right to global rule. Just as his life-span straddled the century, Kipling straddled geographical boundaries and ideological positions, and these inconsistencies come through most prominently, and productively, in his literature.

Kipling alluded directly to this paradoxical duality when he prefaced a chapter in his most famous, provocative and successful novel, Kim (1901), with two short excerpts from a poem entitled 'The Two-Sided Man', in which he thanks "Allah" for "giving me two/Separate sides to my head." Though we should be careful when reading Kipling's literature through a biographical lens, certain decisions Kipling made during his lifetime suggest an ambivalence that gestures towards the schizophrenic nature of his colonial identity. Despite his adamant patriotism and obvious talent for popular poetic composition, Kipling declined an unofficial offer to become, after the death of Alfred Lord Tennyson, Queen Victoria's Poet Laureate in 1892. Despite the jingoistic nationalism that emerged in his poetry towards the end of the nineteenth century, and despite writing poems to mark large public occasions (he wrote his now famous poem 'Recessional' for Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897), Kipling's refusal of the Laureateship suggests a reluctance to fully assume the role of British poet.

What is fascinating about Kipling is that the man who could write The White Man's Burden in 1899, with its blatant and ugly racism ("new-caught sullen peoples,/Half devil and half child") and unquestioned faith in the imperial project, could just two years later write Kim (1901), that intimate exploration of the Indian subcontinent through the eyes of a young Irish orphan, Kimball O'Hara. Befriended and co-opted by the arch-imperial figure of Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), an English-born South African capitalist who imagined a world annexed from corner to corner by white imperial powers, some of Kipling's writing demonstrates a similar ideologically fueled and unquestioning enthusiasm for imperial expansion, and the subsequent economic exploitation of African peoples and the extraction of resources from the continent that went hand in hand with it. But his short stories written a decade earlier are brilliant in their wit and satire as they mock Anglo-Indian society, point out the hypocrisies of the Raj's rule, and cross the boundaries, both geographical and cultural, that separated colonizer and colonized.

In 1907 Rudyard Kipling became the first English writer to receive the Nobel prize for literature. But, in fact, Kipling was not an 'English' writer as such -- indeed, like the Laureateship, he refused the prize so as not to be associated with any national government. Kipling was instead a global writer. His extensive travels, his time spent in different geographical and colonial settings, his constant feeling of being an outsider (one side of his head was always "out of place"), make him arguably one of the first, and richest, post/colonial writers. We should not disregard Kipling for his racism and jingoism, but instead interrogate his literature with the critical lens that postcolonialism offers us. Rather than producing English writing, Kipling authored world writing in English. We might want to think about the implications of this when we also recall that Kipling's poem 'If' (1895) has been consistently voted Britain's favourite poem throughout the twentieth century: Kipling introduces the post/colonial into the very heart of British culture itself.

You are here

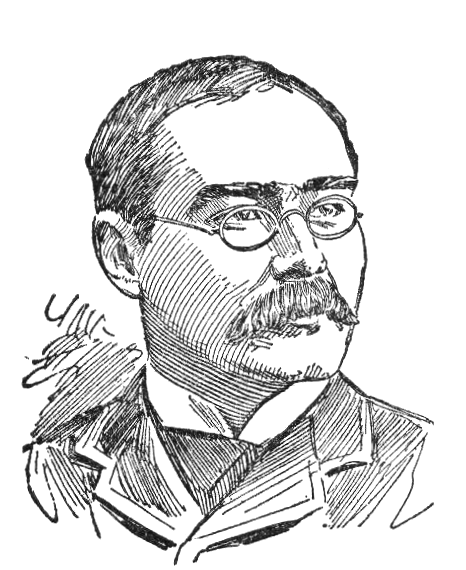

Rudyard Kipling

Please help us improve with this one minute survey (opens in a new tab)

By:

Date Published: 26 June 2012

In Collection(s): Colonial Writers, Rudyard Kipling

Reuse this essay: Download PDF Version | Printer-friendly Version